In 2016, Russia interfered, and it looks like they (and China) may be doing it again. Regardless of which candidate you support, the notion of foreign interference in our election process should make you very concerned. Let's assume that the primary purpose of these governments isn't to get any particular candidate in office. What is their goal then?

Their goal is to create discord and civil unrest, to weaken the U.S. by creating internal strife, and to gain power on the international stage amidst the ensuing chaos. As the adage goes, "a house divided against itself cannot stand."

So what does election interference look like?

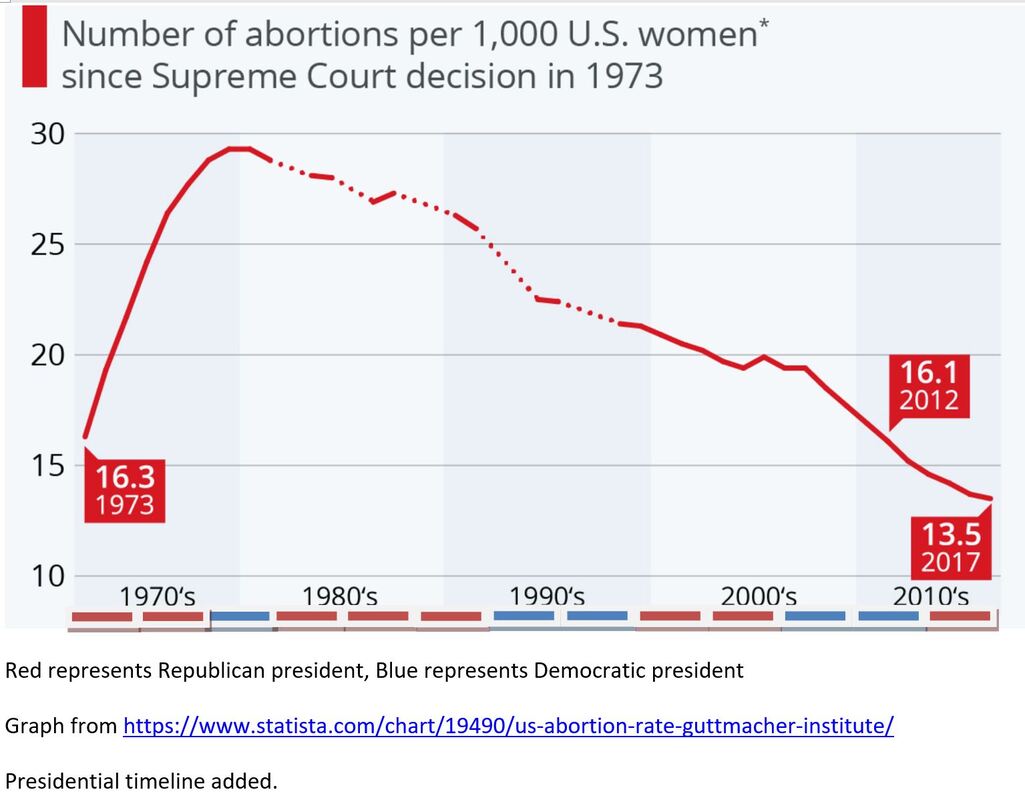

Here's a few examples from the last election:

There's a lesson here - don't trust or share memes and articles unless you know and trust the organizations posting them.

This is not about partisanship, it's about not letting your biases be hacked by foreign meddlers.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed