| Matt Damon has spent a lot of time in space recently. In 2013, it was the sci-fi action movie Elysium. Last year we saw him in Christopher Nolan's epic Interstellar, and now he's completed a trifecta with Ridley Scott's new film, The Martian. Why the emphasis on space flicks? I haven't a clue, but I certainly don't mind. Damon's third extraterrestrial film falls thematically between the other two. Elysium was entertaining but forgettable. Interstellar was existential and philosophical (but may have gone over the heads of some viewers). The Martian, with it's light, witty humor, is entertaining but also profound. It reminded me of Gravity (2013, George Clooney and Sandra Bullock). The Martian is everything you'd expect in a realistic space thriller. The acting is flawless, the cinematography is spectacular and I was white-knuckle gripping my seat on more than one suspenseful occasion |

|

0 Comments

Global life expectancy is on the rise. Since 1990, life expectancy has increased from 65.3 to 71.5. Over the next decade and a half, it is expected to climb another ten years to 81. This average includes countries like the U.S. that have seen a steady increase every year since at least the 1930s, as well as areas like East Asia where life expectancy skyrocketed by thirty years in a short period of time. In other words, it's a great time to be alive!

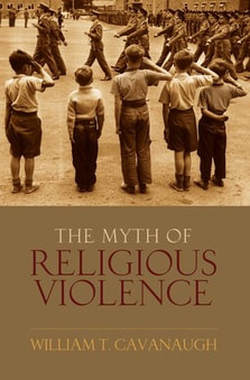

While unexpected deaths still occur even in the most developed countries, they are not nearly as common as they have been throughout history. Accidents, diseases, and infections that once caused sudden death can now be cured or prevented, and despite public perception, deaths caused by war have been in steady decline since the end of the Cold War. As a result, people are are not only living longer, they are dying slower. Medicine and modern health care are able to detect the signs of fatal maladies early on and often slow their progression, effectively easing us gently into the ground.  Book Review: The Myth of Religious Violence by William Cavanaugh (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) In The Myth of Religious Violence, William Cavanaugh argues that the concept of religion as a transhistorical and transcultural entity distinct from secular social features like politics is a mythic construct, not rooted in reality (3). As such, the notion that one can distinguish between violence motivated by religion and violence driven by other cultural, political and social motives is patently false. This is a careful, philosophical book, in which the author takes time to define his terms and explain exactly what his argument is and is not, using more examples than will interest most readers in the cause of being thorough (7). Cavanaugh’s stated goal in writing The Myth of Religious Violence is to show that the distinction between the categories “religious” and “secular” is a false, western, modernist construction that only came into existence with the rise of the secular nation-state (3). Prior to this, religion and governance comingled so that it never occurred to declare violence either religious or non-religious. These categories had not yet been teased apart. By identifying violence with religion, westerners are able construe reality in their favor, creating a false sense of distance between “safe” secular institutions and “dangerous” religious institutions. Yet the ideologies and institutions deemed “secular” can be just as irrational and absolutist as those that are termed religious (6). To prove this thesis, Cavanaugh examines the motives behind the modern separation between politics and religion, showing that the violence occurring in religious communities has the same political and economic motivators as the violence that occurs among political and non-religious institutions. In fact, Cavanaugh goes so far as to say that since it is impossible to distinguish between religious and non-religious violence, the very notion of religious violence is a myth. Cavanaugh replaces this myth with a more nuanced and deeply rooted theory that violence arises from the socio-political, or “theopolitical” aims of various people groups (230). He achieves this through the following four steps. First, Cavanaugh explains the roots of the myth and shows how three common arguments used to defend the link between religion and violence fail (17). These arguments claim that religion causes violence because it is absolutist, divisive, and insufficiently rational (18). Cavanaugh engages nine thinkers who promote these arguments, carefully defeating each in order to make his case. Drawing on the likes of John Hick, Martin Marty, and Richard Wentz, Cavanaugh shows that the distinction between religious and secular violence is based on faulty a priori logic. To refer to religious violence, one must first assume that religious violence can be distinguished from violence arising from other sources. Cavanaugh maintains that this task is impossible. For example, the twentieth century debate over flag burning in the United States was understood as a secular conflict, yet was rife with language presenting the flag as a sacred totem that should not be desecrated. These secular claims are identical to the claims religious adherents make about their sacred objects (55). Despite the supposedly secular status, patriotism and the belief in the righteousness of one’s own national cause often results in the same absolutist, divisive and irrational behaviors blamed on religion. Cavanaugh’s purpose in this example is not to show the similarities between religious and secular violence, but to show that the evidence does not substantiate a distinction between religious and secular violence. Rather, the roots of violence are the same regardless of whether a conflict is termed religious or secular (56). Cavanaugh’s second step is to explain the invention of religion as a transhistorical, transcultural entity. He wants to show that attempts to differentiate between the religious and the secular are based on false distinctions. To do this, he deconstructs essentialist definitions of religion, whether they take substantivist (religion is defined as awareness of the Transcendent) or functionalist (religion is that which includes certain practices) approaches (58). Cavanaugh points out that all such approaches fundamentally fail because there is no universally recognizable “essence of religion” (58). It is, in fact, “a constructed category” that only exists when used diametrically in opposition to the term “secular” (58). Moreover, the defining characteristics used by leading scholars of religion are simply arbitrary (59). Cavanaugh asks why certain configurations of power lead to denoting some things as religions, that in other circumstances are not considered religions. For example, Confucianism is often defined as a religion by Westerners, but its Eastern adherents regard it as irreligious (119). This leads to an appropriate question: “what practices and shifts in power occur when religion is so construed?” One such power shift is the validation of the nation state. When religion is considered to be categorically different than secular institutions, a negative bias is created against religion and secular institutions are then presented as unquestionably neutral and thus worthy of allegiance in a way that religion is not. Thus religion becomes “part of the legitimating mythology of the modern liberal state” (122). It is not a transcultural, transhistorical entity in and of itself. Third, Cavanaugh examines what he calls the wars of religion myth (120). The term “wars of religion” applies to a number of conflicts between Catholics and Lutherans following the Protestant Reformation. Proponents of the wars of religion term claim that these were conflicts between two branches of Christianity, and therefore were religiously motivated. Cavanaugh points out that the truth is much more complicated. During these conflicts, Catholics often killed other Catholics, Lutherans other Lutherans, and so on (11). As such, the roots of violence included not only religious affiliation, but also political, economic, and social factors, and it is unclear how these factors should be weighted. The rise of the nation state is commonly posed as the necessary triumph of secular policing institutions that made peace between warring religious factions in 16th and 17th century Europe. Cavanaugh argues that this presentation of the raw elements of history serves primarily as a myth legitimizing the use of force by nation-states (124). But the transfer of power from the church to the state did not result in a more peaceful Europe; it simply changed what people were willing to commit violence for (12). Rather than presenting the “religious wars” as secular, as other scholars have attempted to do, Cavanaugh argues that they were the origin of the religious/secular distinction and thus the source of the myth of religious violence (124). To make this case he draws on Spinoza, Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, as well as current historiography and political theory to explain how these wars came to be presented this way. Additionally, he notes that it is impossible to separate the religious goals of violence from political, economical, or social goals. In fact, it was often the attempt to achieve political or state power that caused much of the violence of the so-called “religious wars” (177). Therefore the religious wars do not promote the myth of religious violence, but in fact, are a primary source of the myth. Fourth and finally, Cavanaugh looks to the uses of the religious myth. Using a wide range of historical and contemporary resources, he shows how the myth of religious violence has served to both justify and overlook atrocities performed in the name of nation states (228). “Religious beliefs do not lurk essentially unchanged underneath historical circumstances, waiting to unleash their destructive power on the world” (229). This is because no transcultural, transhistorical and essentialist religion exists. In a telling example, Cavanaugh points out that it was the CIA , invoking military action against Russia during the Cold War, that reawakened the concept of jihad. Prior to U.S. action in 1979, jihad had been dormant for close to four hundred years (230). In using the U.S. involvement in Afghanistan, Cavanaugh is again reinforcing that religious and nonreligious action cannot be separated. Instead, he prefers the term “theopolitical,” and notes that all violence is best understood this way (230). In order to understand violence holistically, Cavanaugh proposes a test: “Under what conditions do certain beliefs and practices – jihad, the ‘invisible hand’ of the market the sacrificial atonement of Christ, the role of the United States as worldwide liberator – turn violent?” (8). When we neglect this question, we fail to understand the nuances and complexities of the forces that shape history and create violence. Cautious readers would do well to recognize Cavanaugh’s catholic faith as a powerful motivator in this project, for it is possible that his faith could predetermine his supposition that the religious/secular divide is an artificial construct. That being noted, his argument is strongly supported, easy to follow, and well organized. A professor of theology at DePaul University in Chicago, Cavanaugh also holds a law degree and has spent a portion of his career working for the Center for Human and Civil Rights at Notre Dame University. This unique constellation of experiences confirms Cavanaugh’s capability to undertake this bold project that challenges popular assumptions about the connections between religion and violence. Recently, a friend told me he was really excited about a new yoga class he was going to, but after a few weeks he started feeling guilty about going. I asked him why, and he said that yoga made him feel uncomfortably selfish. "Yoga makes my mind and body so relaxed and invigorated at the same time, I would do it every day if I could. But that's the problem. I feel selfish doing something that's 'just for me." The implication is that if something makes me feel that good, it must be wrong. I must be stealing a good from someone else to make it happen. Maybe you feel that way. You have a favorite activity that makes you feel alive and awake, like the world is a good and beautiful place to exist. But at the same time, you feel a nagging guilty feeling. Somewhere in your past, a parent, a mentor, a spiritual leader or teacher told you that you were being selfish. That you should be more responsible. That there is no room for passion and play in the adult world. We all carry these wounds. Sometimes they were inflicted by people with the best of intentions: "Give up on music, and get a real job. You'll never make it anyways." "Travel is a waste of time." It can even be something small, like "Don't paint your apartment, you're just going to have to repaint it when you move out" (I'm guilty of that one). This kind of advice often comes from people who foreclosed on their own dreams a long time ago, and you might be bringing up old hurts with your dreams. Squishing your dreams with "reality" is less painful than mourning the dreams they gave up a long time ago. But the universe is not a zero sum game. Pursuing your passions doesn't mean you are being irresponsible or neglecting some greater good in society. It's not a pie with a limited amount of slices. When you do something that makes you feel alive, you're not stealing the last slice of goodness from someone who doesn't have any. Nothing could be farther from the truth. The universe is expanding. When you pursue your passions, whether it's yoga, higher education, art, music, gardening or any number of other things, you are creating good in the world and in yourself. The books you enjoy only exist because someone shut themselves away for a few months to pound out their ideas on a keyboard. The art class you are taking is only possible because someone devoted themselves to a craft and became an expert through years of practice. The spiritual leaders whose wisdom keeps you on track cultivate their thoughts in solitude and prayer. This is not a new idea. The greatest men and women in history have understood this. You have nothing to offer humanity, if you yourself are empty and shallow. It's the same principle lifeguards use when saving people in the ocean, or that flight attendants tell you on airplanes in case of emergency. You have to take care of yourself to care for others. As you seek wonder and experience beauty, you will become an oasis that draws and nourishes others. When you treat yourself to something that makes you feel alive, you are doing something that heals and gives life to the soul. You are not selfish, you are bringing joy to the world. It is only by being yourself, that you have anything to offer. It is in your passion, as you flourish, that you can best love your neighbor and help them flourish.

Take care of yourself. Fill the world with life. Live in freedom, and make the world a better place. |

Intersecting is a blog that explores the connections between religion, philosophy, politics, film, psychology, science... and everything else

Innovation is found at the intersection of ideas, concepts and cultures

-The Medici Effect If the medicine is good, the disease will be cured. It is not necessary to know who prepared it, or where it came from -Walpola Rahula When you water the root of the tree, that water naturally extends to every branch and every leaf and every flower on that tree. So when we actually find the origin of true pleasure, in feeling the infinite sweet love that God has for us, and in realizing our potential to love God, that love naturally extends to all living beings. -Radhanath Swami Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed